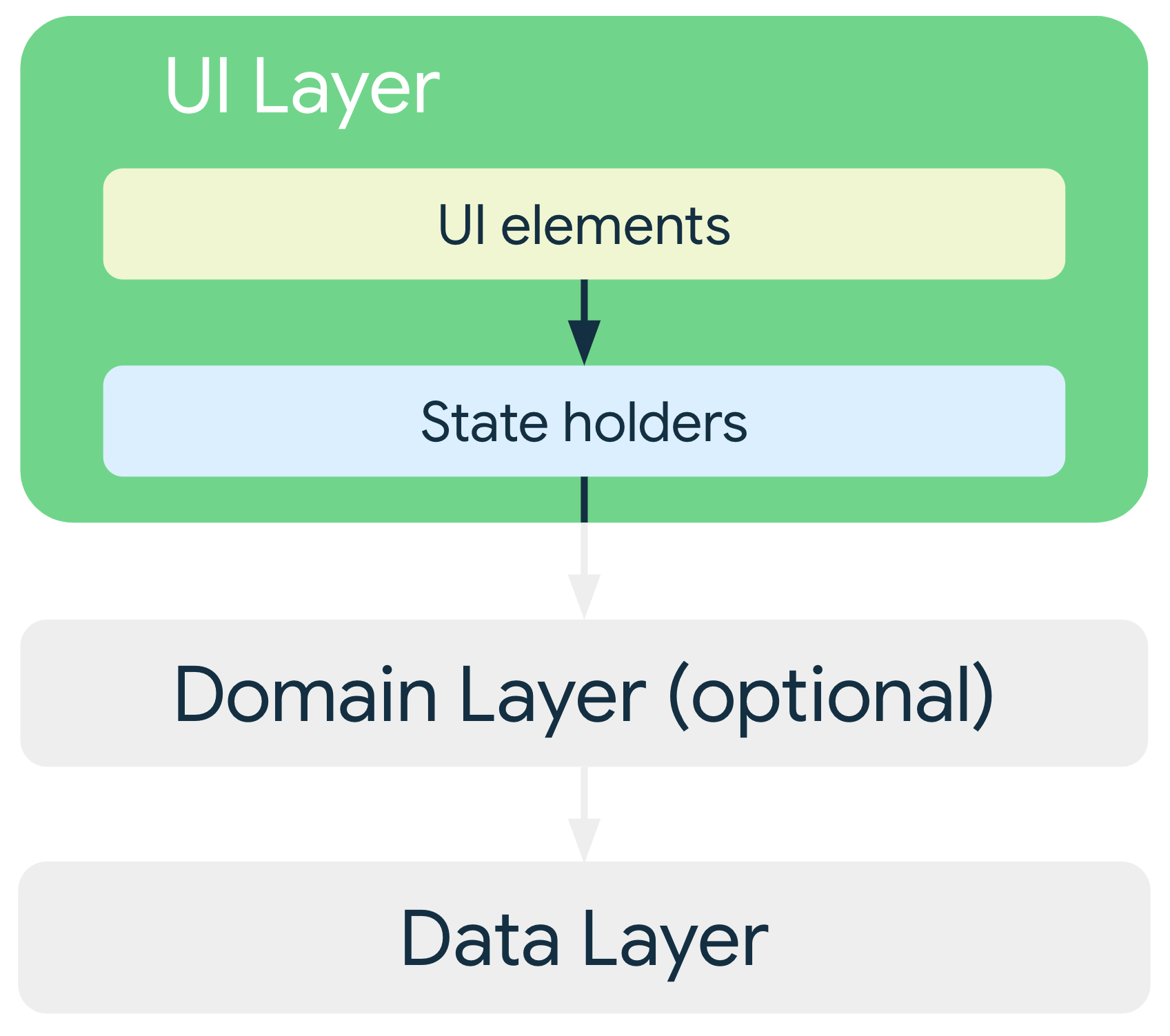

The role of the UI is to display the application data on the screen and also to serve as the primary point of user interaction. Whenever the data changes, either due to user interaction (like pressing a button) or external input (like a network response), the UI should update to reflect those changes. Effectively, the UI is a visual representation of the application state as retrieved from the data layer.

However, the application data you get from the data layer is usually in a different format than the information you need to display. For example, you might only need part of the data for the UI, or you might need to merge two different data sources to present information that is relevant to the user. Regardless of the logic you apply, you need to pass the UI all the information it needs to render fully. The UI layer is the pipeline that converts application data changes to a form that the UI can present and then displays it.

A basic case study

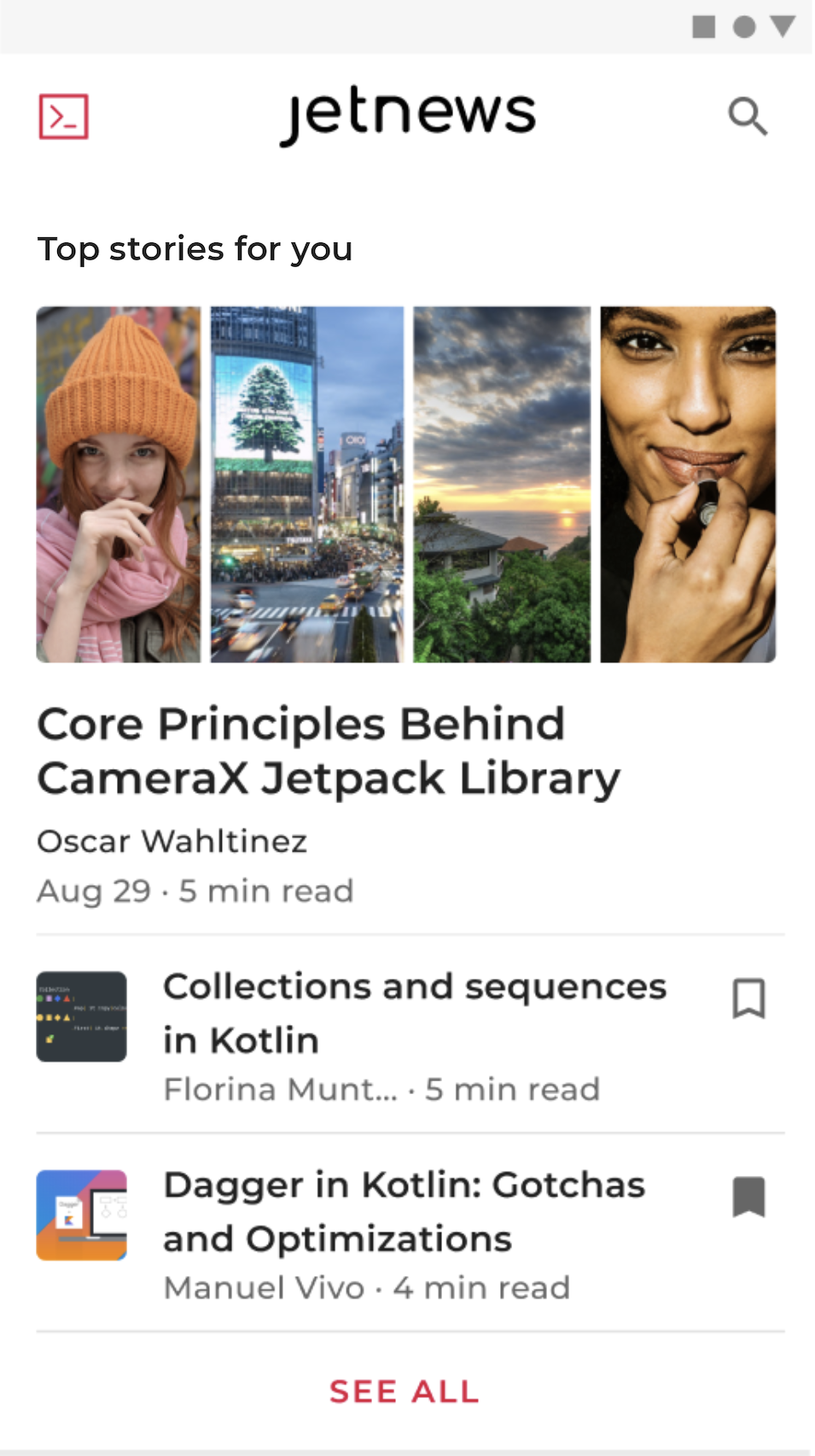

Consider an app that fetches news articles for a user to read. The app has an articles screen that presents articles available to read, and also allows signed-in users to bookmark articles that really stand out. Given that there may be a lot of articles at any moment in time, the reader should be able to browse articles by category. In summary, the app lets users do the following:

- View articles available to read.

- Browse articles by category.

- Sign in and bookmark certain articles.

- Access some premium features if eligible.

The following sections use this example as a case study to introduce the principles of unidirectional data flow, as well as illustrating the problems that these principles help solve in the context of app architecture for the UI layer.

UI layer architecture

The term UI refers to UI elements such as activities and fragments that display the data, independent of what APIs they use to do this (Views or Jetpack Compose). Because the role of the data layer is to hold, manage, and provide access to the app data, the UI layer must perform the following steps:

- Consume app data and transform it into data the UI can easily render.

- Consume UI-renderable data and transform it into UI elements for presentation to the user.

- Consume user input events from those assembled UI elements and reflect their effects in the UI data as needed.

- Repeat steps 1 through 3 for as long as necessary.

The rest of this guide demonstrates how to implement a UI layer that performs these steps. In particular, this guide covers the following tasks and concepts:

- How to define the UI state.

- Unidirectional data flow (UDF) as a means of producing and managing the UI state.

- How to expose UI state with observable data types according to UDF principles.

- How to implement UI that consumes the observable UI state.

The most fundamental of these is the definition of the UI state.

Define UI state

Refer to the case study outlined earlier. In short, the UI shows a list of articles along with some metadata for each article. This information that the app presents to the user is the UI state.

In other words: if the UI is what the user sees, the UI state is what the app says they should see. Like two sides of the same coin, the UI is the visual representation of the UI state. Any changes to the UI state are immediately reflected in the UI.

Consider the case study; in order to fulfill the News app's requirements, the

information required to fully render the UI can be encapsulated in a

NewsUiState data class defined as follows:

data class NewsUiState(

val isSignedIn: Boolean = false,

val isPremium: Boolean = false,

val newsItems: List<NewsItemUiState> = listOf(),

val userMessages: List<Message> = listOf()

)

data class NewsItemUiState(

val title: String,

val body: String,

val bookmarked: Boolean = false,

...

)

Immutability

The UI state definition in the example above is immutable. The key benefit of this is that immutable objects provide guarantees regarding the state of the application at an instant in time. This frees up the UI to focus on a single role: to read the state and update its UI elements accordingly. As a result, you should never modify the UI state in the UI directly unless the UI itself is the sole source of its data. Violating this principle results in multiple sources of truth for the same piece of information, leading to data inconsistencies and subtle bugs.

For example, if the bookmarked flag in a NewsItemUiState object from the UI

state in the case study were updated in the Activity class, that flag would be

competing with the data layer as the source of the bookmarked status of an

article. Immutable data classes are very useful for preventing this kind of

antipattern.

Naming conventions in this guide

In this guide, UI state classes are named based on the functionality of the screen or part of the screen they describe. The convention is as follows:

functionality + UiState.

For example, the state of a screen displaying news might be called

NewsUiState, and the state of a news item in a list of news items might be a

NewsItemUiState.

Manage state with Unidirectional Data Flow

The previous section established that the UI state is an immutable snapshot of the details needed for the UI to render. However, the dynamic nature of data in apps means that state might change over time. This might be due to user interaction or other events that modify the underlying data that is used to populate the app.

These interactions may benefit from a mediator to process them, defining the logic to be applied to each event and performing the requisite transformations to the backing data sources in order to create UI state. These interactions and their logic may be housed in the UI itself, but this can quickly get unwieldy as the UI starts to become more than its name suggests: it becomes data owner, producer, transformer, and more. Furthermore, this can affect testability because the resulting code is a tightly coupled amalgam with no discernable boundaries. Ultimately, the UI stands to benefit from reduced burden. Unless the UI state is very simple, the UI's sole responsibility should be to consume and display UI state.

This section discusses Unidirectional Data Flow (UDF), an architecture pattern that helps enforce this healthy separation of responsibility.

State holders

The classes that are responsible for the production of UI state and contain the necessary logic for that task are called state holders. State holders come in a variety of sizes depending on the scope of the corresponding UI elements that they manage, ranging from a single widget like a bottom app bar to a whole screen or a navigation destination.

In the latter case, the typical implementation is an instance of a

ViewModel, although depending on the

requirements of the application, a simple class might suffice. The News app from

the case study, for example, uses a NewsViewModel class as a

state holder to produce the UI state for the screen displayed in that section.

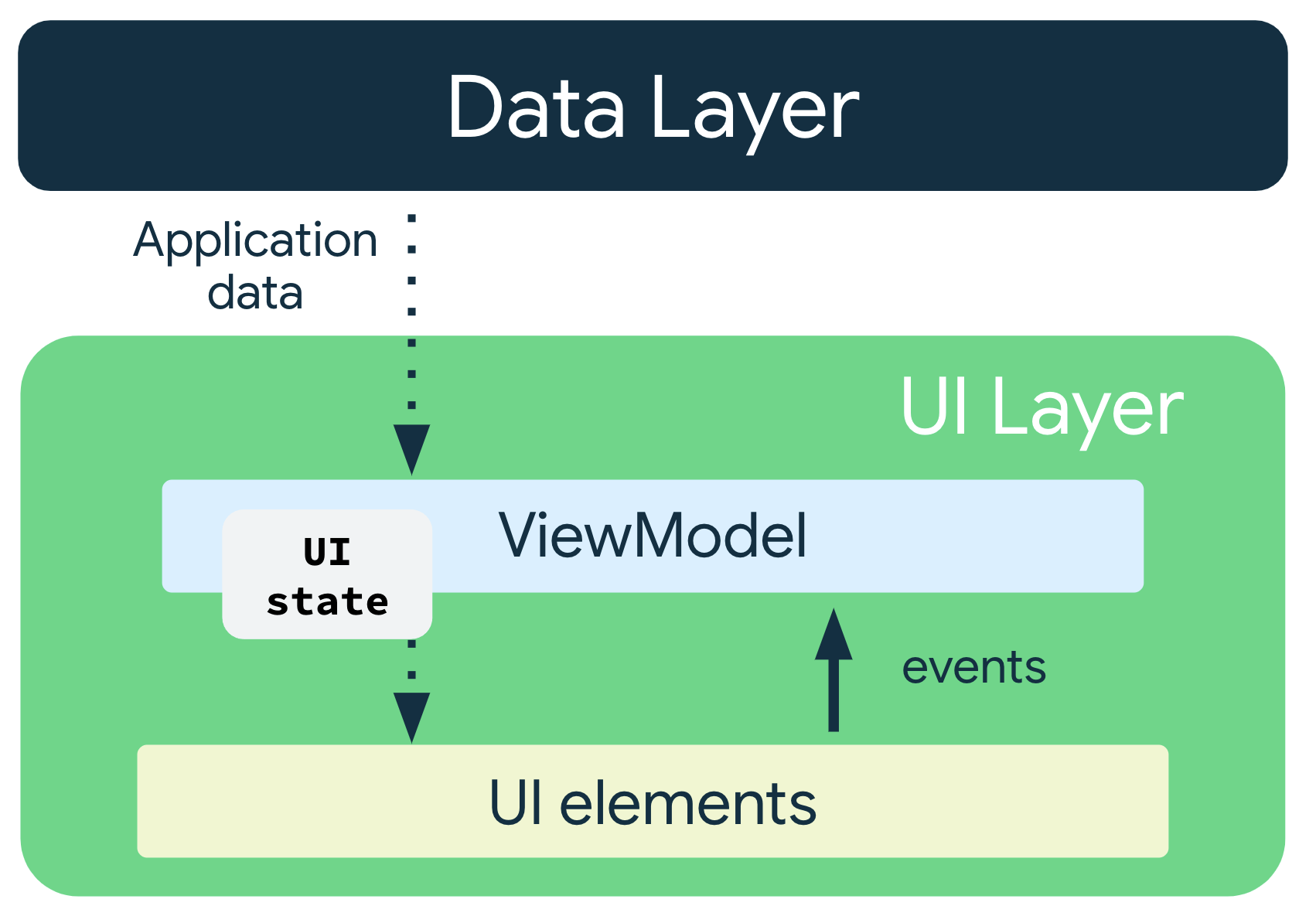

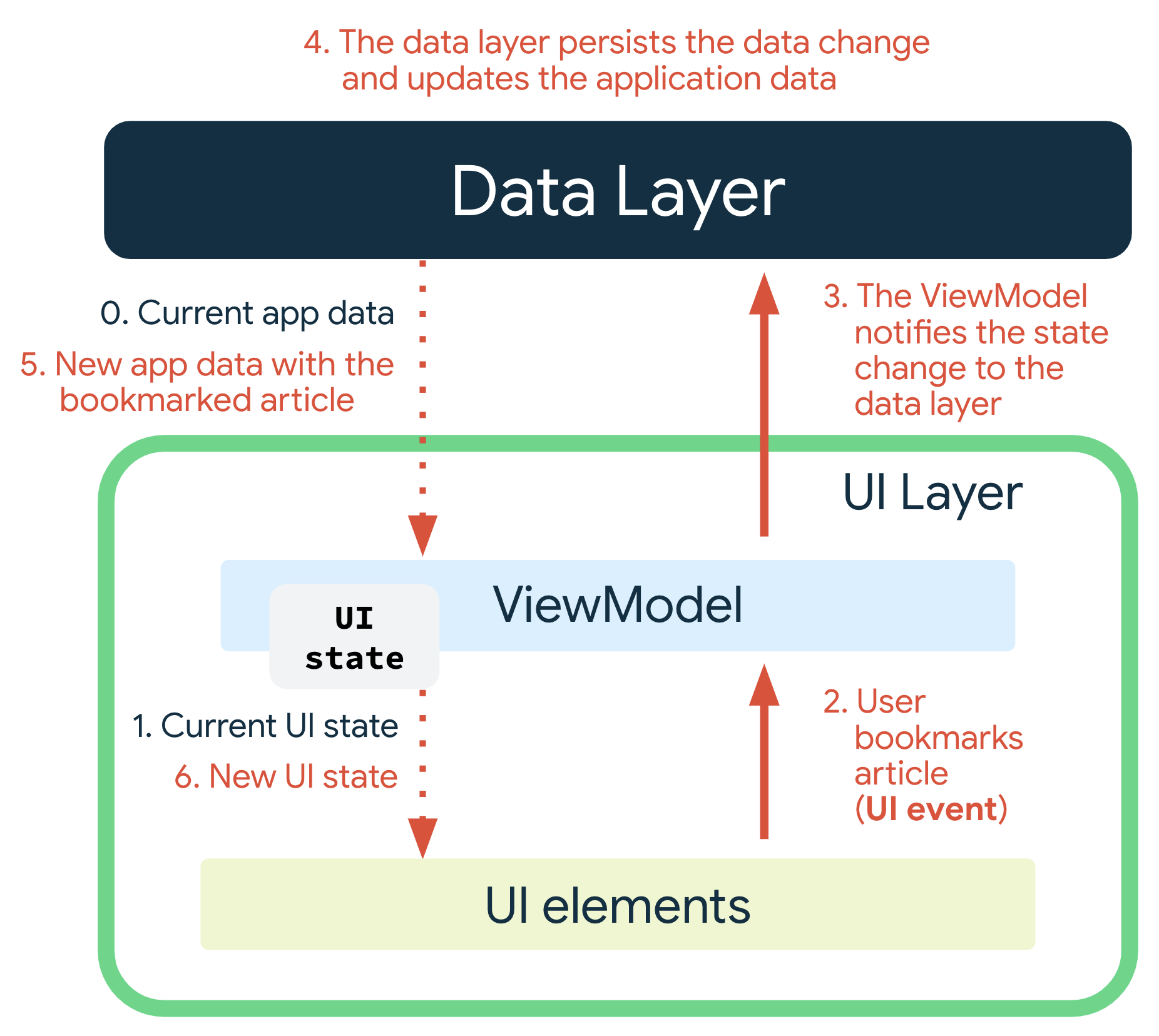

There are many ways to model the codependency between the UI and its state

producer. However, because the interaction between the UI and its ViewModel

class can largely be understood as event input and its ensuing state output,

the relationship can be represented as shown in the following diagram:

The pattern where the state flows down and the events flow up is called a unidirectional data flow (UDF). The implications of this pattern for app architecture are as follows:

- The ViewModel holds and exposes the state to be consumed by the UI. The UI state is application data transformed by the ViewModel.

- The UI notifies the ViewModel of user events.

- The ViewModel handles the user actions and updates the state.

- The updated state is fed back to the UI to render.

- The above is repeated for any event that causes a mutation of state.

For navigation destinations or screens, the ViewModel works with repositories or use case classes to get data and transform it into the UI state while incorporating the effects of events that may cause mutations of the state. The case study mentioned earlier contains a list of articles, each having a title, description, source, author name, publication date, and whether it was bookmarked. The UI for each article item looks like this:

A user requesting to bookmark an article is an example of an event that can cause state mutations. As the state producer, it's the ViewModel’s responsibility to define all the logic required in order to populate all fields in the UI state and process the events needed for the UI to render fully.

The following sections take a closer look at the events that cause state changes and how they can be processed using UDF.

Types of logic

Bookmarking an article is an example of business logic because it gives value to your app. To learn more about this, see the data layer page. However, there are different types of logic that are important to define:

- Business logic is the implementation of product requirements for app data. As mentioned already, one example is bookmarking an article in the case study app. Business logic is usually placed in the domain or data layers, but never in the UI layer.

- UI behavior logic or UI logic is how to display state changes on

the screen. Examples include obtaining the right text to show on the screen

using Android

Resources, navigating to a particular screen when the user clicks a button, or displaying a user message on the screen using a toast or a snackbar.

The UI logic, particularly when it involves UI types like

Context, should live in the UI, not in

the ViewModel. If the UI grows in complexity and you want to delegate the UI

logic to another class to favor testability and separation of concerns, you

can create a simple class as a state holder. Simple classes created in the UI

can take Android SDK dependencies because they follow the lifecycle of the UI;

ViewModel objects have a longer lifespan.

For more information about state holders and how they fit into the context of helping build UI, see the Jetpack Compose State guide.

Why use UDF?

UDF models the cycle of state production as shown in Figure 4. It also separates the place where state changes originate, the place where they are transformed, and the place where they are finally consumed. This separation lets the UI do exactly what its name implies: display information by observing state changes, and relay user intent by passing those changes on to the ViewModel.

In other words, UDF allows for the following:

- Data consistency. There is a single source of truth for the UI.

- Testability. The source of state is isolated and therefore testable independent of the UI.

- Maintainability. Mutation of state follows a well-defined pattern where mutations are a result of both user events and the sources of data they pull from.

Expose UI state

After you define your UI state and determine how you will manage the production

of that state, the next step is to present the produced state to the UI. Because

you're using UDF to manage the production of state, you can consider the

produced state to be a stream—in other words, multiple versions of the state

will be produced over time. As a result, you should expose the UI state in an

observable data holder like LiveData or StateFlow. The reason for this is so

that the UI can react to any changes made in the state without having to

manually pull data directly from the ViewModel. These types also have the

benefit of always having the latest version of the UI state cached, which is

useful for quick state restoration after configuration changes.

Views

class NewsViewModel(...) : ViewModel() {

val uiState: StateFlow<NewsUiState> = …

}

Compose

class NewsViewModel(...) : ViewModel() {

val uiState: NewsUiState = …

}

For an introduction to LiveData as an observable data holder, see this

codelab. For a similar

introduction to Kotlin flows, see Kotlin flows on Android.

In cases where the data exposed to the UI is relatively simple, it's often worth wrapping the data in a UI state type because it conveys the relationship between the emission of the state holder and its associated screen or UI element. Furthermore, as the UI element grows more complex, it’s always easier to add to the definition of the UI state to accommodate the extra information needed to render the UI element.

A common way of creating a stream of UiState is by exposing a backing mutable

stream as an immutable stream from the ViewModel—for example, exposing a

MutableStateFlow<UiState> as a StateFlow<UiState>.

Views

class NewsViewModel(...) : ViewModel() {

private val _uiState = MutableStateFlow(NewsUiState())

val uiState: StateFlow<NewsUiState> = _uiState.asStateFlow()

...

}

Compose

class NewsViewModel(...) : ViewModel() {

var uiState by mutableStateOf(NewsUiState())

private set

...

}

The ViewModel can then expose methods that internally mutate the state,

publishing updates for the UI to consume. Take, for example, the case where an

asynchronous action needs to be performed; a coroutine can be launched using the

viewModelScope, and

the mutable state can be updated upon completion.

Views

class NewsViewModel(

private val repository: NewsRepository,

...

) : ViewModel() {

private val _uiState = MutableStateFlow(NewsUiState())

val uiState: StateFlow<NewsUiState> = _uiState.asStateFlow()

private var fetchJob: Job? = null

fun fetchArticles(category: String) {

fetchJob?.cancel()

fetchJob = viewModelScope.launch {

try {

val newsItems = repository.newsItemsForCategory(category)

_uiState.update {

it.copy(newsItems = newsItems)

}

} catch (ioe: IOException) {

// Handle the error and notify the UI when appropriate.

_uiState.update {

val messages = getMessagesFromThrowable(ioe)

it.copy(userMessages = messages)

}

}

}

}

}

Compose

class NewsViewModel(

private val repository: NewsRepository,

...

) : ViewModel() {

var uiState by mutableStateOf(NewsUiState())

private set

private var fetchJob: Job? = null

fun fetchArticles(category: String) {

fetchJob?.cancel()

fetchJob = viewModelScope.launch {

try {

val newsItems = repository.newsItemsForCategory(category)

uiState = uiState.copy(newsItems = newsItems)

} catch (ioe: IOException) {

// Handle the error and notify the UI when appropriate.

val messages = getMessagesFromThrowable(ioe)

uiState = uiState.copy(userMessages = messages)

}

}

}

}

In the above example, the NewsViewModel class attempts to fetch articles for a

certain category and then reflects the result of the attempt—whether success or

failure—in the UI state where the UI can react to it appropriately. See the

Show errors on the screen section to learn more about error

handling.

Additional considerations

In addition to the previous guidance, consider the following when exposing UI state:

A UI state object should handle states that are related to each other. This leads to fewer inconsistencies and it makes the code easier to understand. If you expose the list of news items and the number of bookmarks in two different streams, you might end up in a situation where one was updated and the other was not. When you use a single stream, both elements are kept up to date. Furthermore, some business logic may require a combination of sources. For example, you might need to show a bookmark button only if the user is signed in and that user is a subscriber to a premium news service. You could define a UI state class as follows:

data class NewsUiState( val isSignedIn: Boolean = false, val isPremium: Boolean = false, val newsItems: List<NewsItemUiState> = listOf() ) val NewsUiState.canBookmarkNews: Boolean get() = isSignedIn && isPremiumIn this declaration, the visibility of the bookmark button is a derived property of two other properties. As business logic gets more complex, having a singular

UiStateclass where all properties are immediately available becomes increasingly important.UI states: single stream or multiple streams? The key guiding principle for choosing between exposing UI state in a single stream or in multiple streams is the previous bullet point: the relationship between the items emitted. The biggest advantage to a single-stream exposure is convenience and data consistency: consumers of state always have the latest information available at any instant in time. However, there are instances where separate streams of state from the ViewModel might be appropriate:

Unrelated data types: Some states that are needed to render the UI might be completely independent from each other. In cases like these, the costs of bundling these disparate states together might outweigh the benefits, especially if one of these states is updated more frequently than the other.

UiStatediffing: The more fields there are in aUiStateobject, the more likely it is that the stream will emit as a result of one of its fields being updated. Because views don't have a diffing mechanism to understand whether consecutive emissions are different or the same, every emission causes an update to the view. This means that mitigation using theFlowAPIs or methods likedistinctUntilChanged()on theLiveDatamight be necessary.

Consume UI state

To consume the stream of UiState objects in the UI, you use the terminal

operator for the observable data type that you're using. For example, for

LiveData you use the observe() method, and for Kotlin flows you use the

collect() method or its variations.

When consuming observable data holders in the UI, make sure you take the

lifecycle of the UI into consideration. This is important because the UI

shouldn’t be observing the UI state when the view isn’t being displayed to the

user. To learn more about this topic, see this blog

post.

When using LiveData, the LifecycleOwner implicitly takes care of lifecycle

concerns. When using flows, it's best to handle this with the appropriate

coroutine scope and the repeatOnLifecycle API:

Views

class NewsActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

private val viewModel: NewsViewModel by viewModels()

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

...

lifecycleScope.launch {

repeatOnLifecycle(Lifecycle.State.STARTED) {

viewModel.uiState.collect {

// Update UI elements

}

}

}

}

}

Compose

@Composable

fun LatestNewsScreen(

viewModel: NewsViewModel = viewModel()

) {

// Show UI elements based on the viewModel.uiState

}

Show in-progress operations

A simple way to represent loading states in a UiState class is with a

boolean field:

data class NewsUiState(

val isFetchingArticles: Boolean = false,

...

)

This flag's value represents the presence or absence of a progress bar in the UI.

Views

class NewsActivity : AppCompatActivity() {

private val viewModel: NewsViewModel by viewModels()

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) {

...

lifecycleScope.launch {

repeatOnLifecycle(Lifecycle.State.STARTED) {

// Bind the visibility of the progressBar to the state

// of isFetchingArticles.

viewModel.uiState

.map { it.isFetchingArticles }

.distinctUntilChanged()

.collect { progressBar.isVisible = it }

}

}

}

}

Compose

@Composable

fun LatestNewsScreen(

modifier: Modifier = Modifier,

viewModel: NewsViewModel = viewModel()

) {

Box(modifier.fillMaxSize()) {

if (viewModel.uiState.isFetchingArticles) {

CircularProgressIndicator(Modifier.align(Alignment.Center))

}

// Add other UI elements. For example, the list.

}

}

Show errors on the screen

Showing errors in the UI is similar to showing in-progress operations because they are both easily represented by boolean values that denote their presence or absence. However, errors might also include an associated message to relay back to the user, or an action associated with them that retries the failed operation. Therefore, while an in-progress operation is either loading or not loading, error states might need to be modeled with data classes that host the metadata appropriate for the context of the error.

For example, consider the example from the previous section which showed a progress bar while fetching articles. If this operation results in an error, you might want to display one or more messages to the user detailing what went wrong.

data class Message(val id: Long, val message: String)

data class NewsUiState(

val userMessages: List<Message> = listOf(),

...

)

The error messages might then be presented to the user in the form of UI elements like snackbars. Because this is related to how UI events are produced and consumed, see the UI events page to learn more.

Threading and concurrency

Any work performed in a ViewModel should be main-safe—safe to call from the main thread. This is because the data and domain layers are responsible for moving work to a different thread.

If a ViewModel performs long-running operations, then it is also responsible for moving that logic to a background thread. Kotlin coroutines are a great way to manage concurrent operations, and the Jetpack Architecture Components provide built-in support for them. To learn more about using coroutines in Android apps, see Kotlin coroutines on Android.

Navigation

Changes in app navigation are often driven by event-like emissions. For example,

after a SignInViewModel class performs a sign-in, the UiState might have an

isSignedIn field set to true. Triggers like these should be consumed just

like the ones covered in the Consume UI state section

above, except that the consumption implementation should defer to the

Navigation component.

Paging

The Paging library is

consumed in the UI with a type called PagingData. Because PagingData

represents and contains items that can change over time—in other words, it is

not an immutable type—it should not be represented in an immutable UI state.

Instead, you should expose it from the ViewModel independently in its own

stream. See the Android Paging codelab for a

specific example of this.

Animations

In order to provide fluid and smooth top-level navigation transitions, you might

want to wait for the second screen to load data before starting the animation.

The Android view framework provides hooks to delay transitions between fragment

destinations with the

postponeEnterTransition()

and

startPostponedEnterTransition()

APIs. These APIs provide a way to ensure that the UI elements on the second

screen (typically an image fetched from the network) are ready to be displayed

before the UI animates the transition to that screen. For more details and

implementation specifics, see the Android Motion

sample.

Samples

The following Google samples demonstrate the use of the UI layer. Go explore them to see this guidance in practice:

Recommended for you

- Note: link text is displayed when JavaScript is off

- UI State production

- State holders and UI State {:#mad-arch}

- Guide to app architecture