As a user navigates through, out of, and back to your app, the

Activity instances in your app transition through

different states in their lifecycle.

The Activity class provides a number of callbacks

that let the activity know when a state changes or that the

system is creating, stopping, or resuming an activity or destroying

the process the activity resides in.

Within the lifecycle callback methods, you can declare how your activity behaves when the user leaves and re-enters the activity. For example, if you're building a streaming video player, you might pause the video and terminate the network connection when the user switches to another app. When the user returns, you can reconnect to the network and let the user resume the video from the same spot.

Each callback lets you perform specific work that's appropriate to a given change of state. Doing the right work at the right time and handling transitions properly make your app more robust and performant. For example, good implementation of the lifecycle callbacks can help your app avoid the following:

- Crashing if the user receives a phone call or switches to another app while using your app.

- Consuming valuable system resources when the user is not actively using it.

- Losing the user's progress if they leave your app and return to it at a later time.

- Crashing or losing the user's progress when the screen rotates between landscape and portrait orientation.

This document explains the activity lifecycle in detail. The document begins by describing the lifecycle paradigm. Next, it explains each of the callbacks: what happens internally while they execute and what you need to implement during them.

It then briefly introduces the relationship between activity state and a process’s vulnerability to being killed by the system. Finally, it discusses several topics related to transitions between activity states.

For information about handling lifecycles, including guidance about best practices, see Handling Lifecycles with Lifecycle-Aware Components and Save UI states. To learn how to architect a robust, production-quality app using activities in combination with architecture components, see Guide to app architecture.

Activity-lifecycle concepts

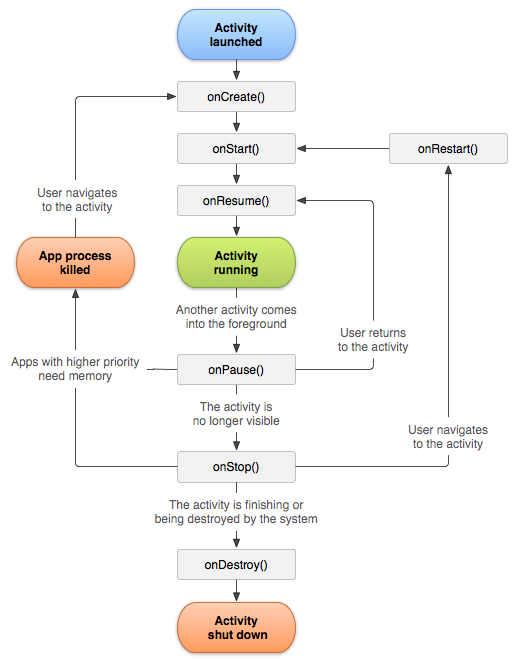

To navigate transitions between stages of the activity lifecycle, the

Activity class provides a core set of six callbacks:

onCreate(),

onStart(),

onResume(),

onPause(),

onStop(), and

onDestroy(). The system invokes

each of these callbacks as the activity enters a new state.

Figure 1 presents a visual representation of this paradigm.

Figure 1. A simplified illustration of the activity lifecycle.

As the user begins to leave the activity, the system calls methods to dismantle the activity. In some cases, the activity is only partially dismantled and still resides in memory, such as when the user switches to another app. In these cases, the activity can still come back to the foreground.

If the user returns to the activity, it resumes from where the user left off. With a few exceptions, apps are restricted from starting activities when running in the background.

The system’s likelihood of killing a given process, along with the activities in it, depends on the state of the activity at the time. For more information on the relationship between state and vulnerability to ejection, see the section about activity state and ejection from memory.

Depending on the complexity of your activity, you probably don't need to implement all the lifecycle methods. However, it's important that you understand each one and implement those that make your app behave the way users expect.

Lifecycle callbacks

This section provides conceptual and implementation information about the callback methods used during the activity lifecycle.

Some actions belong in the activity lifecycle methods. However, place code that implements the actions of a dependent component in the component, rather than the activity lifecycle method. To achieve this, you need to make the dependent component lifecycle-aware. To learn how to make your dependent components lifecycle-aware, see Handling Lifecycles with Lifecycle-Aware Components.

onCreate()

You must implement this callback, which fires when the system first creates the

activity. On activity creation, the activity enters the Created state.

In the onCreate()

method, perform basic application startup logic that

happens only once for the entire life of the activity.

For example, your

implementation of onCreate() might bind data to lists, associate the activity with a

ViewModel,

and instantiate some class-scope variables. This method receives the

parameter savedInstanceState, which is a Bundle

object containing the activity's previously saved state. If the activity has

never existed before, the value of the Bundle object is null.

If you have a lifecycle-aware component that is hooked up to the lifecycle of

your activity, it receives the

ON_CREATE

event. The method annotated with @OnLifecycleEvent is called so your lifecycle-aware

component can perform any setup code it needs for the created state.

The following example of the onCreate() method

shows fundamental setup for the activity, such as declaring the user interface

(defined in an XML layout file), defining member variables, and configuring

some of the UI. In this example, the XML layout file passes the

file’s resource ID R.layout.main_activity to

setContentView().

Kotlin

lateinit var textView: TextView // Some transient state for the activity instance. var gameState: String? = null override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) { // Call the superclass onCreate to complete the creation of // the activity, like the view hierarchy. super.onCreate(savedInstanceState) // Recover the instance state. gameState = savedInstanceState?.getString(GAME_STATE_KEY) // Set the user interface layout for this activity. // The layout is defined in the project res/layout/main_activity.xml file. setContentView(R.layout.main_activity) // Initialize member TextView so it is available later. textView = findViewById(R.id.text_view) } // This callback is called only when there is a saved instance previously saved using // onSaveInstanceState(). Some state is restored in onCreate(). Other state can optionally // be restored here, possibly usable after onStart() has completed. // The savedInstanceState Bundle is same as the one used in onCreate(). override fun onRestoreInstanceState(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) { textView.text = savedInstanceState?.getString(TEXT_VIEW_KEY) } // Invoked when the activity might be temporarily destroyed; save the instance state here. override fun onSaveInstanceState(outState: Bundle?) { outState?.run { putString(GAME_STATE_KEY, gameState) putString(TEXT_VIEW_KEY, textView.text.toString()) } // Call superclass to save any view hierarchy. super.onSaveInstanceState(outState) }

Java

TextView textView; // Some transient state for the activity instance. String gameState; @Override public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { // Call the superclass onCreate to complete the creation of // the activity, like the view hierarchy. super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); // Recover the instance state. if (savedInstanceState != null) { gameState = savedInstanceState.getString(GAME_STATE_KEY); } // Set the user interface layout for this activity. // The layout is defined in the project res/layout/main_activity.xml file. setContentView(R.layout.main_activity); // Initialize member TextView so it is available later. textView = (TextView) findViewById(R.id.text_view); } // This callback is called only when there is a saved instance previously saved using // onSaveInstanceState(). Some state is restored in onCreate(). Other state can optionally // be restored here, possibly usable after onStart() has completed. // The savedInstanceState Bundle is same as the one used in onCreate(). @Override public void onRestoreInstanceState(Bundle savedInstanceState) { textView.setText(savedInstanceState.getString(TEXT_VIEW_KEY)); } // Invoked when the activity might be temporarily destroyed; save the instance state here. @Override public void onSaveInstanceState(Bundle outState) { outState.putString(GAME_STATE_KEY, gameState); outState.putString(TEXT_VIEW_KEY, textView.getText()); // Call superclass to save any view hierarchy. super.onSaveInstanceState(outState); }

As an alternative to defining the XML file and passing it to setContentView(), you

can create new View objects in your activity code and build a

view hierarchy by inserting new View objects into a

ViewGroup. You then use that layout by passing the

root ViewGroup to setContentView().

For more information about creating a user interface, see the

user interface documentation.

Your activity does not remain in the Created

state. After the onCreate() method finishes execution, the activity enters the Started

state and the system calls the onStart()

and onResume() methods in quick

succession.

onStart()

When the activity enters the Started state, the system

invokes onStart().

This call makes the activity visible to the user as the

app prepares for the activity to enter the foreground and become interactive.

For example, this method is where the code that maintains

the UI is initialized.

When the activity moves to the Started state, any lifecycle-aware component tied

to the activity's lifecycle receives the

ON_START event.

The onStart() method completes

quickly and, as with the Created state, the activity does not remain

in the Started state. Once this callback finishes, the activity enters the

Resumed state and the system invokes the

onResume() method.

onResume()

When the activity enters the Resumed state, it comes to the foreground, and

the system invokes the onResume()

callback. This is the state in which the app

interacts with the user. The app stays in this state until something happens to

take focus away from the app, such as the device receiving a phone call, the user

navigating to another activity, or the device screen turning off.

When the activity moves to the Resumed state, any lifecycle-aware component tied

to the activity's lifecycle receives the

ON_RESUME

event. This is where the lifecycle components can enable any functionality that needs to run while

the component is visible and in the foreground, such as starting a camera

preview.

When an interruptive event occurs, the activity enters the Paused

state and the system invokes the

onPause() callback.

If the activity returns to

the Resumed state from the Paused state, the system once again calls the

onResume() method. For this reason, implement

onResume() to initialize components that you release during

onPause() and to perform any other

initializations that must occur each time the activity enters the Resumed

state.

Here is an example of a lifecycle-aware component that accesses the camera when

the component receives the ON_RESUME event:

Kotlin

class CameraComponent : LifecycleObserver { ... @OnLifecycleEvent(Lifecycle.Event.ON_RESUME) fun initializeCamera() { if (camera == null) { getCamera() } } ... }

Java

public class CameraComponent implements LifecycleObserver { ... @OnLifecycleEvent(Lifecycle.Event.ON_RESUME) public void initializeCamera() { if (camera == null) { getCamera(); } } ... }

The preceding code initializes the camera once the

LifecycleObserver

receives the ON_RESUME event. In multi-window mode, however, your activity

might be fully visible even when it is in the Paused state. For example, when

the app is in multi-window mode and the user taps the window that does not

contain your activity, your activity moves to the Paused state.

If you

want the camera active only when the app is Resumed (visible

and active in the foreground), then initialize the camera after the

ON_RESUME event

demonstrated previously. If you want to keep the camera active while the activity

is Paused but visible, such as in multi-window mode, then

initialize the camera after the ON_START event.

However, having the camera active while your activity is Paused might deny access to the camera to another Resumed app in multi-window mode. Sometimes it is necessary to keep the camera active while your activity is Paused, but it might actually degrade the overall user experience if you do.

For this reason, think carefully about where in the lifecycle it is most appropriate to take control of shared system resources in the context of multi-window mode. To learn more about supporting multi-window mode, see Multi-window support.

Regardless of which build-up event you choose to perform an

initialization operation in, make sure to use the corresponding lifecycle

event to release the resource. If you initialize something after

the ON_START event, release or terminate it after the

ON_STOP event. If you

initialize after the ON_RESUME event, release after the

ON_PAUSE event.

The preceding code snippet places camera initialization code in a

lifecycle-aware component. You can instead put this code directly into the activity

lifecycle callbacks, such as onStart() and

onStop(), but we don't recommend this. Adding this logic

to an independent, lifecycle-aware component lets you reuse the component

across multiple activities without having to duplicate code. To learn how to create a lifecycle-aware component, see

Handling Lifecycles with Lifecycle-Aware Components.

onPause()

The system calls this method as the first indication that the user is leaving your activity, though it does not always mean the activity is being destroyed. It indicates that the activity is no longer in the foreground, but it is still visible if the user is in multi-window mode. There are several reasons why an activity might enter this state:

- An event that interrupts app execution, as described in the section about the onResume() callback, pauses the current activity. This is the most common case.

- In multi-window mode, only one app has focus at any time, and the system pauses all the other apps.

- The opening of a new, semi-transparent activity, such as a dialog, pauses the activity it covers. As long as the activity is partially visible but not in focus, it remains paused.

When an activity moves to the Paused state, any lifecycle-aware component tied

to the activity's lifecycle receives the

ON_PAUSE event. This is where

the lifecycle components can stop any functionality that does not need to run

while the component is not in the foreground, such as stopping a camera

preview.

Use the onPause() method to pause or

adjust operations that can't continue, or might continue in moderation,

while the Activity is in the Paused state, and that you

expect to resume shortly.

You can also use the onPause() method to

release system resources, handles to sensors (like GPS), or any resources that

affect battery life while your activity is Paused and the user does not

need them.

However, as mentioned in the section about onResume(), a Paused

activity might still be fully visible if the app is in multi-window mode.

Consider using onStop() instead of onPause() to fully release or adjust

UI-related resources and operations to better support multi-window mode.

The following example of a LifecycleObserver

reacting to the ON_PAUSE event is the counterpart to the preceding

ON_RESUME event example, releasing the camera that initializes after

the ON_RESUME event is received:

Kotlin

class CameraComponent : LifecycleObserver { ... @OnLifecycleEvent(Lifecycle.Event.ON_PAUSE) fun releaseCamera() { camera?.release() camera = null } ... }

Java

public class JavaCameraComponent implements LifecycleObserver { ... @OnLifecycleEvent(Lifecycle.Event.ON_PAUSE) public void releaseCamera() { if (camera != null) { camera.release(); camera = null; } } ... }

This example places the camera release code after the

ON_PAUSE event is received by the LifecycleObserver.

onPause() execution is very brief and

does not necessarily offer enough time to perform save operations. For this

reason, don't use onPause() to save application or user

data, make network calls, or execute database transactions. Such work might not

complete before the method completes.

Instead, perform heavy-load shutdown operations during

onStop(). For more information

about suitable operations to perform during

onStop(), see the next section. For more information about saving

data, see the section about saving and restoring state.

Completion of the onPause() method

does not mean that the activity leaves the Paused state. Rather, the activity

remains in this state until either the activity resumes or it becomes completely

invisible to the user. If the activity resumes, the system once again invokes

the onResume() callback.

If the

activity returns from the Paused state to the Resumed state, the system keeps

the Activity instance resident in memory, recalling

that instance when the system invokes onResume().

In this scenario, you don’t need to re-initialize components created during any of the

callback methods leading up to the Resumed state. If the activity becomes

completely invisible, the system calls

onStop().

onStop()

When your activity is no longer visible to the user, it enters the

Stopped state, and the system invokes the

onStop() callback. This can occur when a newly launched activity covers the entire screen. The

system also calls onStop()

when the activity finishes running and is about to be terminated.

When the activity moves to the Stopped state, any lifecycle-aware component tied

to the activity's lifecycle receives the

ON_STOP event. This is where

the lifecycle components can stop any functionality that does not need to run

while the component is not visible on the screen.

In the onStop() method, release or adjust

resources that are not needed while the app is not visible to the user. For example, your app might

pause animations or switch from fine-grained to coarse-grained location updates. Using

onStop() instead of onPause()

means that UI-related work continues, even when the user is viewing your activity in multi-window

mode.

Also, use onStop()

to perform relatively CPU-intensive shutdown operations. For example, if

you can't find a better time to save information to a database,

you might do so during onStop(). The

following example shows an implementation of

onStop() that saves the contents of a

draft note to persistent storage:

Kotlin

override fun onStop() { // Call the superclass method first. super.onStop() // Save the note's current draft, because the activity is stopping // and we want to be sure the current note progress isn't lost. val values = ContentValues().apply { put(NotePad.Notes.COLUMN_NAME_NOTE, getCurrentNoteText()) put(NotePad.Notes.COLUMN_NAME_TITLE, getCurrentNoteTitle()) } // Do this update in background on an AsyncQueryHandler or equivalent. asyncQueryHandler.startUpdate( token, // int token to correlate calls null, // cookie, not used here uri, // The URI for the note to update. values, // The map of column names and new values to apply to them. null, // No SELECT criteria are used. null // No WHERE columns are used. ) }

Java

@Override protected void onStop() { // Call the superclass method first. super.onStop(); // Save the note's current draft, because the activity is stopping // and we want to be sure the current note progress isn't lost. ContentValues values = new ContentValues(); values.put(NotePad.Notes.COLUMN_NAME_NOTE, getCurrentNoteText()); values.put(NotePad.Notes.COLUMN_NAME_TITLE, getCurrentNoteTitle()); // Do this update in background on an AsyncQueryHandler or equivalent. asyncQueryHandler.startUpdate ( mToken, // int token to correlate calls null, // cookie, not used here uri, // The URI for the note to update. values, // The map of column names and new values to apply to them. null, // No SELECT criteria are used. null // No WHERE columns are used. ); }

The preceding code sample uses SQLite directly. However, we recommend using Room, a persistence library that provides an abstraction layer over SQLite. To learn more about the benefits of using Room and how to implement Room in your app, see the Room Persistence Library guide.

When your activity enters the Stopped state, the Activity

object is kept resident in memory: it maintains all state and member

information, but is not attached to the window manager. When the activity

resumes, it recalls this information.

You don’t need to

re-initialize components created during any of the callback methods

leading up to the Resumed state. The system also keeps track of the current

state for each View object in the layout, so if the

user enters text into an EditText widget, that

content is retained so you don't need to save and restore it.

Note: Once your activity is stopped, the system

might destroy the process that contains the activity if the system

needs to recover memory.

Even if the system destroys the process while the activity

is stopped, the system still retains the state of the View

objects, such as text in an EditText widget, in a

Bundle—a blob of key-value pairs—and restores them

if the user navigates back to the activity. For

more information about restoring an activity to which a user returns, see the

section about saving and restoring state.

From the Stopped state, the activity either comes back to interact with the

user, or the activity is finished running and goes away. If the activity comes

back, the system invokes onRestart().

If the Activity is finished running, the system calls

onDestroy().

onDestroy()

onDestroy() is called before the

activity is destroyed. The system invokes this callback for one of two reasons:

-

The activity is finishing, due to the user completely dismissing the

activity or due to

finish()being called on the activity. - The system is temporarily destroying the activity due to a configuration change, such as device rotation or entering multi-window mode.

When the activity moves to the destroyed state, any lifecycle-aware component tied

to the activity's lifecycle receives the

ON_DESTROY event. This is where

the lifecycle components can clean up anything they need to before the

Activity is destroyed.

Instead of putting logic in your Activity to determine why it is being destroyed,

use a ViewModel object to contain the

relevant view data for your Activity. If the Activity is recreated

due to a configuration change, the ViewModel does not have to do anything, since

it is preserved and given to the next Activity instance.

If the Activity isn't recreated, then the ViewModel has the

onCleared() method called, where

it can clean up any data it needs to before being destroyed. You can distinguish between these two scenarios with the

isFinishing() method.

If the activity is finishing, onDestroy() is the final lifecycle callback the

activity receives. If onDestroy() is called as the result of a configuration

change, the system immediately creates a new activity instance and then calls

onCreate()

on that new instance in the new configuration.

The onDestroy() callback releases all resources not released by earlier

callbacks, such as onStop().

Activity state and ejection from memory

The system kills processes when it needs to free up RAM. The likelihood of the system killing a given process depends on the state of the process at the time. Process state, in turn, depends on the state of the activity running in the process. Table 1 shows the correlations among process state, activity state, and the likelihood of the system killing the process. This table only applies if a process is not running other types of application components.

| Likelihood of being killed | Process state | Final activity state |

|---|---|---|

| Lowest | Foreground (having or about to get focus) | Resumed |

| Low | Visible (no focus) | Started/Paused |

| Higher | Background (invisible) | Stopped |

| Highest | Empty | Destroyed |

Table 1. Relationship between process lifecycle and activity state.

The system never kills an activity directly to free up memory. Instead, it kills the process the activity runs in, destroying not only the activity but everything else running in the process as well. To learn how to preserve and restore your activity's UI state when system-initiated process death occurs, see the section about saving and restoring state.

The user can also kill a process by using the Application Manager, under Settings, to kill the corresponding app.

For more information about processes, see Processes and threads overview.

Saving and restoring transient UI state

A user expects an activity’s UI state to remain the same throughout a configuration change, such as rotation or switching into multi-window mode. However, the system destroys the activity by default when such a configuration change occurs, wiping away any UI state stored in the activity instance.

Similarly, a user expects UI state to remain the same if they temporarily switch away from your app to a different app and then come back to your app later. However, the system can destroy your application’s process while the user is away and your activity is stopped.

When system constraints destroy the activity, preserve the

user’s transient UI state using a combination of

ViewModel,

onSaveInstanceState(),

and/or local storage. To learn more about user expectations compared to system

behavior and how to best preserve complex UI state data across

system-initiated activity and process death, see

Save UI states.

This section outlines what instance state is and how to implement the

onSaveInstance() method, which is a callback on the activity itself. If your

UI data is lightweight, you can use onSaveInstance() alone to persist the UI

state across both configuration changes and system-initiated process death.

But because onSaveInstance() incurs serialization/deserialization costs, in

most cases you use both ViewModel and onSaveInstance(), as

outlined in

Save UI states.

Note: To learn more about configuration changes, how to restrict Activity recreation if needed, and how to react to those configuration changes from the View system and Jetpack Compose, check out the Handle configuration changes page.

Instance state

There are a few scenarios in which your activity is destroyed due to normal app

behavior, such as when the user presses the Back button or your activity

signals its own destruction by calling the

finish()

method.

When your activity is destroyed because the user presses Back

or the activity finishes itself, both the system's and the user's concept of

that Activity instance is gone forever. In these

scenarios, the user's expectation matches the system's behavior, and you do not

have any extra work to do.

However, if the system destroys the activity due to system constraints (such as

a configuration change or memory pressure), then although the actual

Activity

instance is gone, the system remembers that it existed. If the user attempts to

navigate back to the activity, the system creates a new instance of that

activity using a set of saved data that describes the state of the activity

when it was destroyed.

The saved data that the system uses to restore the

previous state is called the instance state. It's a collection of

key-value pairs stored in a Bundle object. By default, the

system uses the Bundle instance state to save information

about each View object in your activity layout, such as

the text value entered into an

EditText widget.

So, if your activity instance is destroyed and recreated, the state of the layout is restored to its previous state with no code required by you. However, your activity might have more state information that you'd like to restore, such as member variables that track the user's progress in the activity.

Note: In order for the Android system to restore the state of

the views in your activity, each view must have a unique ID, supplied by

the android:id attribute.

A Bundle object isn't appropriate for preserving more than a

trivial amount of data, because it requires serialization on the main thread and consumes

system-process memory. To preserve more than a very small amount of data,

take a combined approach to preserving data, using persistent local

storage, the onSaveInstanceState() method, and the

ViewModel class, as outlined in

Save UI states.

Save simple, lightweight UI state using onSaveInstanceState()

As your activity begins to stop, the system calls the

onSaveInstanceState()

method so your activity can save state information to an instance state

bundle. The default implementation of this method saves transient

information about the state of the activity's view hierarchy, such as the

text in an EditText widget or the scroll position of a

ListView widget.

To save additional instance state information for your activity, override

onSaveInstanceState()

and add key-value pairs to the Bundle object that is saved

in the event that your activity is destroyed unexpectedly. When you override

onSaveInstanceState(), you need to call the superclass implementation

if you want the default implementation to save the state of the view hierarchy.

This is shown in the following example:

Kotlin

override fun onSaveInstanceState(outState: Bundle?) { // Save the user's current game state. outState?.run { putInt(STATE_SCORE, currentScore) putInt(STATE_LEVEL, currentLevel) } // Always call the superclass so it can save the view hierarchy state. super.onSaveInstanceState(outState) } companion object { val STATE_SCORE = "playerScore" val STATE_LEVEL = "playerLevel" }

Java

static final String STATE_SCORE = "playerScore"; static final String STATE_LEVEL = "playerLevel"; // ... @Override public void onSaveInstanceState(Bundle savedInstanceState) { // Save the user's current game state. savedInstanceState.putInt(STATE_SCORE, currentScore); savedInstanceState.putInt(STATE_LEVEL, currentLevel); // Always call the superclass so it can save the view hierarchy state. super.onSaveInstanceState(savedInstanceState); }

Note:

onSaveInstanceState() is not

called when the user explicitly closes the activity or in other cases when

finish() is called.

To save persistent data, such as user preferences or data for a database,

take appropriate opportunities when your activity is in the foreground.

If no such opportunity arises, save persistent data during the

onStop() method.

Restore activity UI state using saved instance state

When your activity is recreated after it was previously destroyed, you

can recover your saved instance state from the Bundle that the

system passes to your activity. Both the

onCreate() and

onRestoreInstanceState()

callback methods receive the same Bundle that contains the

instance state information.

Because the onCreate() method is

called whether the system is creating a new instance of your activity

or recreating a previous one, you need to check whether the state Bundle

is null before you attempt to read it. If it is null, then the system

is creating a new instance of the activity, instead of restoring a

previous one that was destroyed.

The following code snippet shows how you can restore some

state data in onCreate():

Kotlin

override fun onCreate(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState) // Always call the superclass first // Check whether we're recreating a previously destroyed instance. if (savedInstanceState != null) { with(savedInstanceState) { // Restore value of members from saved state. currentScore = getInt(STATE_SCORE) currentLevel = getInt(STATE_LEVEL) } } else { // Probably initialize members with default values for a new instance. } // ... }

Java

@Override protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) { super.onCreate(savedInstanceState); // Always call the superclass first // Check whether we're recreating a previously destroyed instance. if (savedInstanceState != null) { // Restore value of members from saved state. currentScore = savedInstanceState.getInt(STATE_SCORE); currentLevel = savedInstanceState.getInt(STATE_LEVEL); } else { // Probably initialize members with default values for a new instance. } // ... }

Instead of restoring the state during

onCreate(), you can choose to implement

onRestoreInstanceState(), which the system calls after the

onStart() method. The system calls

onRestoreInstanceState()

only if there is a saved state to restore, so you do

not need to check whether the Bundle is null.

Kotlin

override fun onRestoreInstanceState(savedInstanceState: Bundle?) { // Always call the superclass so it can restore the view hierarchy. super.onRestoreInstanceState(savedInstanceState) // Restore state members from saved instance. savedInstanceState?.run { currentScore = getInt(STATE_SCORE) currentLevel = getInt(STATE_LEVEL) } }

Java

public void onRestoreInstanceState(Bundle savedInstanceState) { // Always call the superclass so it can restore the view hierarchy. super.onRestoreInstanceState(savedInstanceState); // Restore state members from saved instance. currentScore = savedInstanceState.getInt(STATE_SCORE); currentLevel = savedInstanceState.getInt(STATE_LEVEL); }

Caution: Always call the superclass implementation of

onRestoreInstanceState()

so the default implementation can restore the state of the view hierarchy.

Navigating between activities

An app is likely to enter and exit an activity, perhaps many times, during the app’s lifetime, such as when the user taps the device’s Back button or the activity launches a different activity.

This section covers topics you need to know to implement successful activity transitions. These topics include starting an activity from another activity, saving activity state, and restoring activity state.

Starting one activity from another

An activity often needs to start another activity at some point. This need arises, for instance, when an app needs to move from the current screen to a new one.

Depending on whether or not your activity wants a result back from the new activity

it’s about to start, you start the new activity using either the

startActivity()

method or the

startActivityForResult()

method. In either case, you pass in an Intent object.

The Intent object specifies either the exact

activity you want to start or describes the type of action you want to perform.

The system selects the appropriate activity for you, which can even be

from a different application. An Intent object can

also carry small amounts of data to be used by the activity that is started.

For more information about the Intent class, see

Intents and Intent

Filters.

startActivity()

If the newly started activity does not need to return a result, the current activity can start it

by calling the

startActivity()

method.

When working within your own application, you often need to simply launch a known activity.

For example, the following code snippet shows how to launch an activity called

SignInActivity.

Kotlin

val intent = Intent(this, SignInActivity::class.java) startActivity(intent)

Java

Intent intent = new Intent(this, SignInActivity.class); startActivity(intent);

Your application might also want to perform some action, such as send an email, text message, or status update, using data from your activity. In this case, your application might not have its own activities to perform such actions, so you can instead leverage the activities provided by other applications on the device, which can perform the actions for you.

This is where intents are really valuable. You can create an intent that describes an action you want to perform, and the system launches the appropriate activity from another application. If there are multiple activities that can handle the intent, then the user can select which one to use. For example, if you want to let the user send an email message, you can create the following intent:

Kotlin

val intent = Intent(Intent.ACTION_SEND).apply { putExtra(Intent.EXTRA_EMAIL, recipientArray) } startActivity(intent)

Java

Intent intent = new Intent(Intent.ACTION_SEND); intent.putExtra(Intent.EXTRA_EMAIL, recipientArray); startActivity(intent);

The EXTRA_EMAIL extra added to the intent is a string array of

email addresses the email is to be sent to. When an email application

responds to this intent, it reads the string array provided in the extra and

places the addresses in the "to" field of the email composition form. In this

situation, the email application's activity starts, and when the user is done,

your activity resumes.

startActivityForResult()

Sometimes you want to get a result back from an activity when it ends. For example, you might start

an activity that lets the user pick a person in a list of contacts. When it ends, it returns the

person that was selected. To do this, you call the

startActivityForResult(Intent, int)

method, where

the integer parameter identifies the call.

This identifier is meant to distinguish between multiple calls to

startActivityForResult(Intent, int)

from the same activity. It's not a global identifier

and is not at risk of conflicting with other apps or activities. The result comes back through your

onActivityResult(int, int, Intent)

method.

When a child activity exits, it can call setResult(int) to

return data to its parent.

The child activity must supply a result code, which can be the standard results

RESULT_CANCELED, RESULT_OK, or any custom values

starting at RESULT_FIRST_USER.

In addition,

the child activity can optionally return an Intent

object containing any additional data it wants. The parent activity uses the

onActivityResult(int, int, Intent)

method, along with the integer identifier the parent activity originally

supplied, to receive the information.

If a child activity fails for any reason, such as crashing, the parent

activity receives a result with the code RESULT_CANCELED.

Kotlin

class MyActivity : Activity() { // ... override fun onKeyDown(keyCode: Int, event: KeyEvent?): Boolean { if (keyCode == KeyEvent.KEYCODE_DPAD_CENTER) { // When the user center presses, let them pick a contact. startActivityForResult( Intent(Intent.ACTION_PICK,Uri.parse("content://contacts")), PICK_CONTACT_REQUEST) return true } return false } override fun onActivityResult(requestCode: Int, resultCode: Int, intent: Intent?) { when (requestCode) { PICK_CONTACT_REQUEST -> if (resultCode == RESULT_OK) { // A contact was picked. Display it to the user. startActivity(Intent(Intent.ACTION_VIEW, intent?.data)) } } } companion object { internal val PICK_CONTACT_REQUEST = 0 } }

Java

public class MyActivity extends Activity { // ... static final int PICK_CONTACT_REQUEST = 0; public boolean onKeyDown(int keyCode, KeyEvent event) { if (keyCode == KeyEvent.KEYCODE_DPAD_CENTER) { // When the user center presses, let them pick a contact. startActivityForResult( new Intent(Intent.ACTION_PICK, new Uri("content://contacts")), PICK_CONTACT_REQUEST); return true; } return false; } protected void onActivityResult(int requestCode, int resultCode, Intent data) { if (requestCode == PICK_CONTACT_REQUEST) { if (resultCode == RESULT_OK) { // A contact was picked. Display it to the user. startActivity(new Intent(Intent.ACTION_VIEW, data)); } } } }

Coordinating activities

When one activity starts another, they both experience lifecycle transitions. The first activity stops operating and enters the Paused or Stopped state, while the other activity is created. In case these activities share data saved to disc or elsewhere, it's important to understand that the first activity is not completely stopped before the second one is created. Rather, the process of starting the second one overlaps with the process of stopping the first one.

The order of lifecycle callbacks is well defined, particularly when the two activities are in the same process—in other words, the same app—and one is starting the other. Here's the order of operations that occur when Activity A starts Activity B:

- Activity A's

onPause()method executes. - Activity B's

onCreate(),onStart(), andonResume()methods execute in sequence. Activity B now has user focus. - If Activity A is no longer visible on screen, its

onStop()method executes.

This sequence of lifecycle callbacks lets you manage the transition of information from one activity to another.